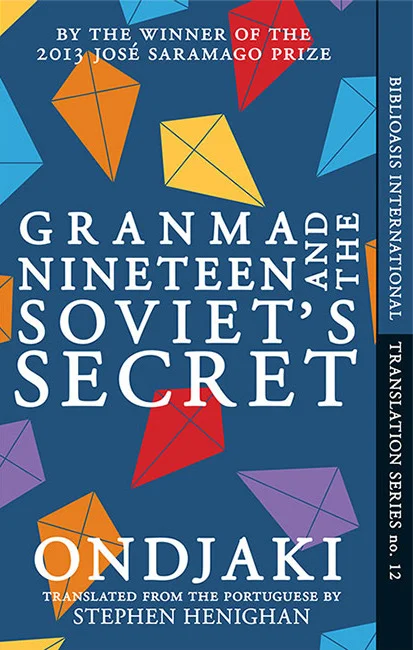

Angola: Granma Nineteen and the Soviet's Secret (Ondjaki, trans. Stephen Henighan)

Ndalu de Almeida, also known as Ondjaki, (b.1977) was born in Luanda, Angola. First studying sociology at the University of Lisbon, he later traveled to Italy for his Doctorate in African Studies. He began to publish in 2000 with a book of poetry, following it with a memoir, and later novels as well as children’s books. He has also made a documentary film. He has won many awards for his work, including the Grinzane for Africa Prize, the Premio Jabuti de Literatura, and the José Saramago Prize.

Background: Inhabited since the paleolithic era, the San people were the first to settle. In the 6th century AD, the Bantu arrived, already having knowledge of metal-working, ceramics, and agriculture. Over the next centuries, various ethnic groups coalesced and in the 13th century, the Kingdom of Kongo began to build and grow. Their power was primarily in agriculture, in the hands of the aristocrats and the king. The Kingdom was made up of six provinces. In 1482, the Portuguese arrived, and trade began: firearms and technology for slaves, ivory, and mineral. The Portuguese established the colony of Angola in 1575 when a hundred families arrived from Europe. Luanda was the capital by 1605. South of the Kingdom of the Kongo, other states existed, including the Kingdom of Ndongo. They were much better at fending off the Portuguese, especially under Queen Jinga, who formed a coalition with her neighbors. When Spain took over Portugal, the Dutch occupied Luanda in 1641 and allied with Queen Jinga. The Portuguese eventually retook Luanda and the Kingdom of Ndongo was defeated in 1671. Until the slate trade was abolished in 1836, trade was active with Brazil. Once foreign shipping took over in 1844, Luanda exported widely. Once the Portuguese monarchy fell, reform took place in administration and education. In 1951, Angola became a province. At the same time, the Portuguese were deeply racist and failed to educate, build infrastructure, or modernize. Protests began in the 1950s, eventually turned to guerrilla warfare against the Portuguese, and in 1975, the country finally gained independence after a coup in Lisbon. Civil war broke out, as factions competed for power. Various foreign countries, such as Cuba and the USA supported different factions as battles continued. In 1987, negotiations for a peaceful solution began and in 1991, the Bicesse Accord was reached, which directed a process for a democratic Angola. Elections did sway the opposition, and war broke out once again in 1992. Finally, in 1994, the Lusaka Protocol, a new peace accord, was signed. Fighting resumed in 1997, and arms deals with Eastern Europe only added fuel to the fire. After years of fighting, yet another Memorandum of Understanding was signed in 2002. The civil war displaced four million people, and many landmines were left over, still being removed. The country has begun to stabilize, and a new constitution was adopted in 2010, however significant humanitarian crises have continued, including a drought in 2016 which affected 1.4 million people.

Granma Nineteen and the Soviet’s Secret is told from the perspective of a child growing up in 1980s Luanda. Both the Cubans and the Soviets have large military presences, and the latter has been active in building a large mausoleum for the previous head of state. The narrator lives with his grandmother, hanging out with a group of other kids, who basically run as they please. As rumors spread that the town will be blown up to make space for the monument, the kids must form a plan to stop the Soviets. At the same time, one of the narrator’s Granmas needs a toe removed, even as another is being fawned over by one of the Soviet officers, Bilhardov. Hijinks ensue, as the children plan to detonate the mausoleum with dynamite to save the town, but their plan may not be as secret as they think. A fun book, and rather brief, Granma Nineteen is not striking in any way, but nor is it a bad read. While many of the novels I’ve read from Africa have been quite heavy, the story’s perspective (from that of a child) dwindles the serious repercussions of what is implied by the possible destruction in the book. Nothing is taken so seriously, and humor pervades. I enjoyed the usage of Portuguese sprinkled throughout, the small glimpses into Angola’s culture, and, to be honest, reading a book from Africa that didn’t leave me feeling totally emotionally drained. At the same time, I wish the gravity of what is going on in the book was more clear. I’m glad I have another book from Angola to balance with this one.